This text by Martine Letarte was published in Le Devoir on September 4, 2021

Ensuring universal access to quality education is the fourth of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. While enrolment in primary schools in developing countries reached 91%, 57 million children are still not in school. Over half of these children are in Sub-Saharan Africa, and one in two is living in an area affected by conflict. To bring about real change, the Girls’ Education for a Better Future in the Great Lakes Region project was started in 2020.

Families decide to stop sending their girls to school so that they can focus on domestic chores and look after their younger brothers. A teenager gets pregnant after being forced to marry and stops going to school to look after her baby. This is what often happens in families in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“The sociocultural burden, due to difficult economic circumstances, is one of the major factors that explains why families in remote areas choose to send boys to school and keep girls home so that they can look after the children,” says Nicole Nyangolo, Regional Coordinator of the Girls’ Education Project for a Better Future in the African Great Lakes Region (EDUFAM) within the Concertation of Collectives of Women’s Associations in the Great Lakes (COCAFEM/GL), who was reached in Bujumbura, Burundi.

For the United Nations, ensuring universal access to quality education based on equality and promoting opportunities for lifelong learning create socioeconomic mobility and a way to overcome poverty.

Moreover, Africa is crucial for the future of French in the world. Of the estimated 300 million Francophones in 2018, some 235 million lived in French, and 60% were in Africa, according to the Organisation internationale de la francophonie.

Adapting to local realities

To promote girls’ schooling, Global Affairs Canada is funding the EDUFAM project led by a consortium that brings together the Centre for International Studies and Cooperation (CECI) for its expertise in gender equality and the Fondation Paul Gérin-Lajoie for its expertise in education. Both organizations work closely with various partners on the ground, coordinated by COCAFEM/GL.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the project is being deployed in Fizi, where the Lusenda refugee camp is located; in Rwanda, in the district of Kirehe, where the Mahama camp is located; and in Burundi, in the Gasorwe commune, where the Kinama camp is located. The project targets 24 schools in three regions where at least 33% of young and adolescent girls do not know how to read or write. “We take a holistic approach, which is why we’re working with several partners in a regional strategy adapted to local realities,” says Coline Camier, Project Manager at CECI.

Removing the obstacles

To put together a list of all the obstacles to girls’ attending school, project workers sat down with the host communities and the refugee communities in the three regions. The communities then signed social contracts in which they committed to reducing these obstacles. “It’s not only parents who are involved, but the entire community. For example, neighbours keep an eye on the girls and if they see a girl who’s not going to school, they go talk to the parents. There’s a very strong sense of community,” says Coline Camier.

A census was also conducted among 19,000 young and adolescent girls in the three regions to provide a portrait of their vulnerabilities. For example, if a family is experiencing major financial difficulties, if a young girl is at risk of being married off early or if a girl has been raped. “Then, we develop an individualized plan for each girl by bringing in a circle of loved ones, key players and the school in order to create an inclusive and safe school environment,” says Ms. Camier.

Efforts are also being made to strengthen women’s leadership. “They’re often in the background, but it’s important that they be visible and vocal. The stronger their presence in schools, the more confident and safer girls will feel,” says Nicole Nyangolo.

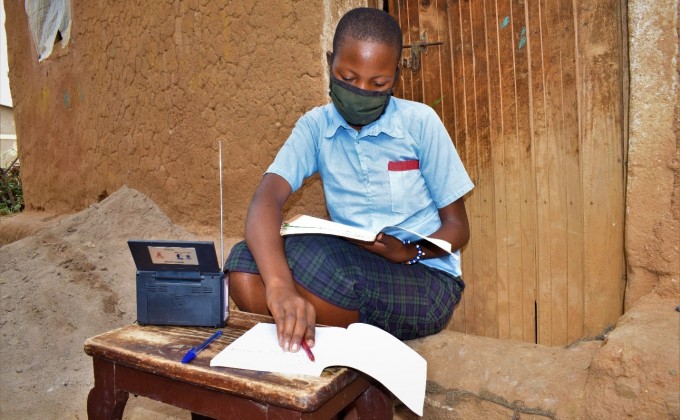

The pandemic has created more obstacles to girls’ education. “COVID-19 complicated everyone’s lives in 2020. Families were already hesitating to send their daughters to school, but things have gotten worse with the current economic situation. In preparation for the return to school in a few days, we have redoubled our efforts to educate people about the importance of sending girls to school,” says Nicole Nyangolo.

The whole community benefits from educating its girls

If the whole community benefits from educating girls, it also pays the price for keeping them out of school. “Girls who go to school can earn up to twice as much as those who don’t get an education, so the impact on their lives and their families is huge, especially given that the value of education is passed on from generation to generation,” says Coline Camier.

Girls’ education also significantly reduces violence, such as forced marriages and genital mutilation. “The more educated people are, the easier it is to fight systemic violence and gender stereotypes. Sending girls to school also helps to improve health, because they have a better understanding of diseases like HIV and malaria. They also learn more about nutrition, among other things. In the end, a country’s entire development depends on the education of girls,” says Coline Camier.